International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Biotechnology

Citation: IJAEB: 13(4): 395-402, December 2020

DOI: 10.30954/0974-1712.04.2020.3

ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE

Impact of Covid - 19 on Food Purchasing, Eating Behaviors and Perceptions of Food Safety in Consumers of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh of India

ABSTRACT

Covid-19 brought a paradigm shift on food consumption, purchase, and eating behavior of consumers significantly as concerns over safety, health, and financial worries increased. As the world was fighting the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic, an online survey is conducted to understand its impact on food purchasing, eating behaviors, and perceptions of food safety among the middle class and upper-middle population in the states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh of India during April and May 2020. Many of the respondents were from Telangana (46.52%) and Andhra Pradesh (38.58%), respectively while few were from other states and countries. 60.7% of respondents who participated in the survey were from the urban areas, while 20.1% were from rural areas and 17% from semi-urban areas. A significant change is observed in consumers’ purchase behavior during the Covid-19 pandemic. People preferred to shop less frequently, and 62% of respondents managed with existing goods. 69% of people maintained social distancing and wearing masks while purchasing foods. 74.3% went to stores less often for groceries purchase. The amount of packaged food consumption increased by 28%. Consumers became more cautious about health and altered their eating habits. 60% of respondents have agreed that their food habits have changed, and 52% of respondents reportedly consumed healthier foods compared to pre-covid days. 90% of survey populations finished home-cooked meals. 96% of respondents were aware of the Covid-19 threat and were taking precautionary measures. 86% of respondents sanitized the food produce bought from outside. There was panic among 53% of respondents about the safety of food available. 34% of respondents did not want to go back to their old eating habits until they get vaccinated against covid-19.

Highlights

Purchasing and eating habits have changed. People were shopping less in-person and consuming more home-cooked healthy meals while managing with existing stocks.

Purchasing and eating habits have changed. People were shopping less in-person and consuming more home-cooked healthy meals while managing with existing stocks.

Consumer behavior changed rapidly throughout, for the crisis. Food consumption, and eating habits, have been significantly impacted due to concerns about hygiene, personal safety, food purchases, and consumption.

Consumer behavior changed rapidly throughout, for the crisis. Food consumption, and eating habits, have been significantly impacted due to concerns about hygiene, personal safety, food purchases, and consumption.

Keywords: COVID-19, Food consumption, Eating Behavior, Food Safety, Precautionary Measures

The covid-19 pandemic caused by a novel coronavirus is currently a major global human threat that has its existence in more than 180 countries across the globe (Zhu et al. 2020). Coronavirus mainly targets the human respiratory system with symptoms like pneumonia, cough, fever, and sometimes is asymptomatic, leading the subject to be a carrier of the virus (Bogoch et al. 2020). Experiences from previous outbreaks have shown that as an epidemic evolves, an immediate extension of public health activities beyond direct clinical management is put into force to manage and optimize resource utilization (Gamage et al. 2009). Since the onset of Covid-19, individual and community resilience emerged in all the nations to improve the efficacy of Covid-19 management in all spheres (Reissman et al. 2006).

How to cite this article: Kuna, A. and Kata, L. (2020). Impact of Covid -19 on Food Purchasing, Eating Behaviors and Perceptions of Food Safety in Consumers of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh of India. IJAEB, 13(4): 395–402.

Source of Support: None; Conflict of Interest: None

As the pandemic spreads, the interaction between individuals and the nourishment framework is changing at an unfathomable speed and taking on more prominent significance in the standard of living. Shopping for food is the only point of contact during the lockdown period as strict rules were set on people's movement to restrain the spread of Covid-19. Indeed so, grocery stores, merchants, and markets have ended up as a confronting barometer of the scale of the pandemic. The root cause of unhealthiness is bad eating habits. Lack of specific action on nutrition, all forms of undernourishment are likely to augment due to the pandemic's influence on food environments (UNSCN, 2020).

The nutritional status of individuals for long considered an essential indicator of resilience against destabilization. The ecology of adversity and resilience demonstrates that substantial stressors, such as inadequate nutrition, can lead to long-lasting effects on both physical and mental health (Cobb, 2001). As massive lockdowns were implemented, we have watched urban poor and migrant workers scrambling for food and basic needs; while the middle and upper-middle class confined to their homes witnessed a change in food purchase and consumption patterns, mainly due to concerns covering both health and financial worries. The consumers were always trying to be more health-conscious with the available budget.

Covid - 19 brought a paradigm shift on the food consumption and purchase behavior of consumers, enormously as concerns over safety, health, and financial worries increased. Consumers became more health-conscious and were also concerned about the environment and comfort, both of which had an impact on eating habits too. Consumers wanted to maximize their health to boost their immunity and reduce vulnerability to the coronavirus. As the world was fighting the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic, an online survey is conducted during April - May 2020 to understand its impact on food purchasing, eating behaviors, and perceptions of food safety among the middle class and upper-middle population in the states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh of India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A questionnaire is designed with 25 questions consisting of demographic details, food purchase, eating behavior, and food safety aspects. An online survey was conducted from 17th April 2020 to 17th May 2020 among 604 adult respondents aged 18+ to ensure proportional results. The questionnaire is specifically built explicitly by using google form and disseminated through institutional and private social networks. The margin of error was ± 3.99% at a 95% confidence level. Statistical significance in this present work should be compared within each demographic (e.g., age, race, gender, etc.), as the results cannot be attributed to random chance. For example, if the responses from female respondents are significant, it is in relation to male respondents and not necessarily other demographic groups.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

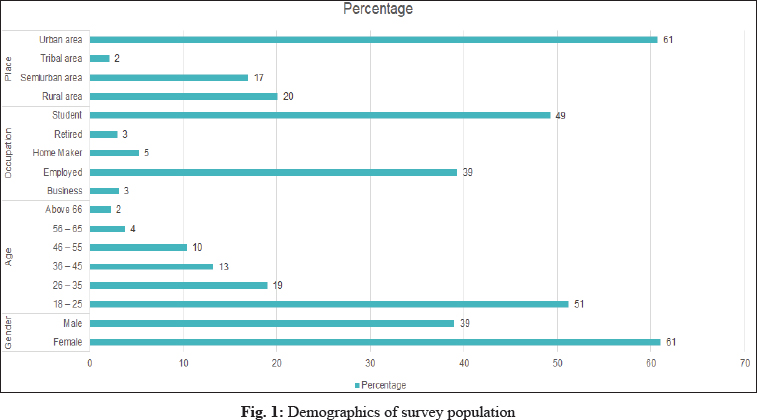

The responses received from Telangana and Andhra Pradesh were 46.52% and 38.58%, while most of the remaining 11.75% were from neighboring Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Maharastra states. 3.14% of Indians residing in other countries also responded to the questionnaire, considering the situations faced by their people living in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. 60.7% of respondents who participated in the survey were from the urban areas, while 20.1% were from rural areas and 17% from semi-urban areas. The majority (51.2%) of the respondents were in the age group of 18 - 25 years, followed by 19% and 13.2% of respondents in the age group 26 - 35 years and 36 - 45 years, respectively. Significantly few respondents in the age groups from 46 to above 66 years participated in the survey. Among them, 49.2% were students, 39.4% were retired people, and 61% were female, and 39% were male. The remaining respondents were either involved in business or were homemakers or retired people (Fig. 1).

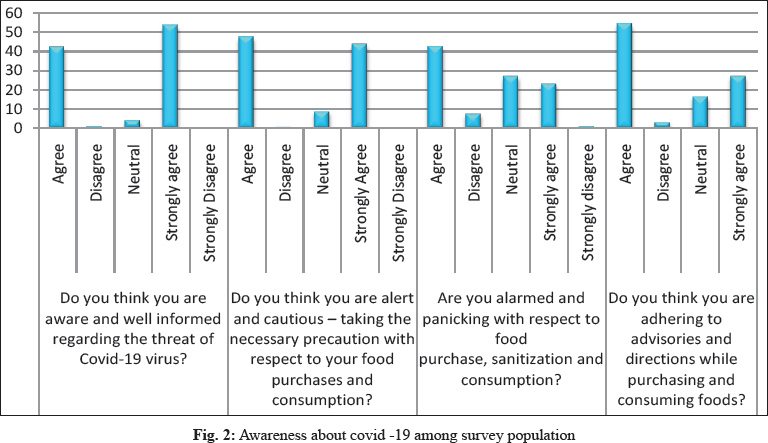

Almost all the respondents who participated in the survey either agreed (53.5%) or strongly agreed (42.1%) that they are well informed regarding the threat of the covid-19 virus. 47.4% and 43.4% of respondents felt that they were alert and cautious in taking necessary precautions concerning their food purchases and consumption (Fig. 2).

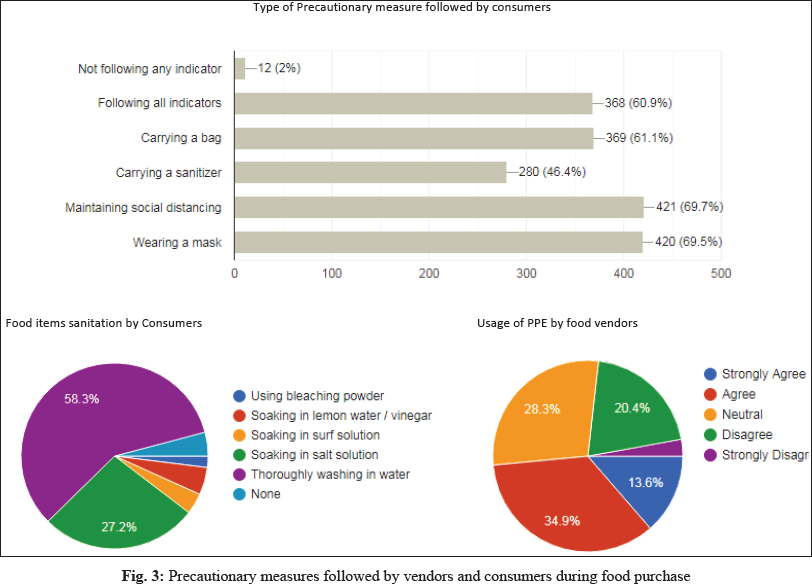

When food purchase and sanitization measures are concerned, 42.4% of the respondents were neither alarmed nor panicked with while 26.7% and 22.8% agreed that they were scared and panicked with their food purchase, sanitization measures. 54% and 27% of respondents were firmly adhering to all the advisories and directions while purchasing foods, while 16.1% were neutral to the advisories and guidelines while buying their foods. Almost 69% of respondents were maintaining social distancing and wearing a mask while buying foods, while 60.9% to 61.1% of respondents were following all the guidelines to buy foods like carrying a bag while they go out to purchase foods (Fig. 3).

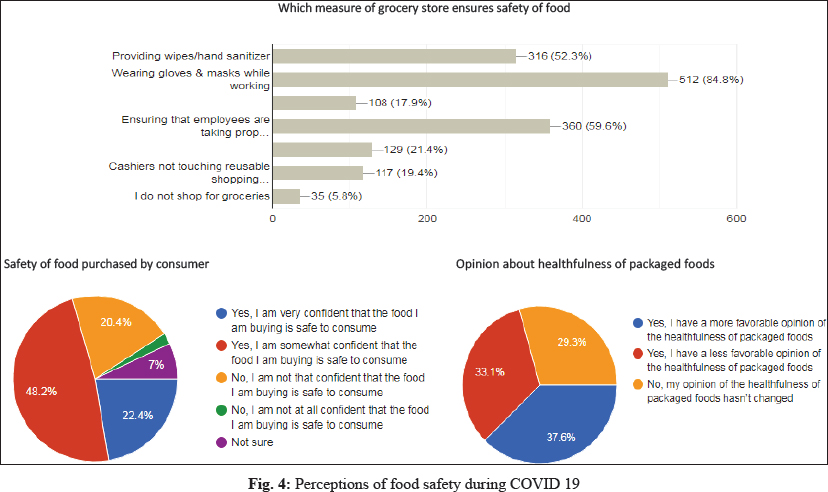

The majority of the respondents felt that the vendors selling foods were wearing personal protection accessories like masks, gloves, etc. Still, almost 20% of respondents thought that the vendors were not wearing sufficient personal protection equipment. About 60% of respondents felt that their food habits have changed over the past two months due to the covid-2019 conditions. They thought they were either shopping less and managing with existing stocks (61.6%) or shopping at stores with less crowd (57.6%). Responses about the safety measures taken at grocery stores by the employees indicate that good care is earned to ensure food safety through measures like wearing gloves and masks while working (84.8%), maintaining proper physical distancing while working (59.9%), providing wipes/ sanitizers (52.3%), installing clear plastic barriers between cashiers and customers (21.4%).

Previous reports on outbreaks, particularly MERS-coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and SARS-coronavirus (SARS- CoV) which are related to coronaviruses indicated that food wasn't a route of transmission of these viruses (Galanakis 2020). However, Rizou et al. (2020) reported that current coronavirus transmission appears to be possible on fresh food products (eg. Vegetables, fruits, or bakery) or food packaging if infected person sneezes or coughs on them. The virus is transferred shortly afterward via the hands (or) the food itself to the mucous membranes of the mouth. Another study by Pung et al. (2020) in Singapore presented that physical contact and sharing common food during a conference resulted in a cluster of covid-19 patients. To minimize the risk from touching food potentially exposed to coronavirus, handling of packages and goods should be followed by hand washing or using hand sanitizer (Seymour et al. 2020). Our study demonstrated that the consumers are aware of the safety practices, and the majority of them are following.

In response to the safety of food, while purchasing groceries, it was observed that 89% of them washed hands regularly after grocery purchase; 74.3% went to stores less often for groceries; 73.1% minimized touching surfaces while purchasing groceries; 66.4% used sanitizers/wipes while buying foods; 52.5% rinsed fresh produce and 34.7% remove external packaging after the purchase of foods. For rinsing the fresh foods purchased, 58.3% of respondents thoroughly washed the fresh produce in water, while 27.2% soaked the foods in a salt solution, and few others soaked the fresh produce in either lemon water or vinegar or surf solution. There were also 26.6% of respondents who made no changes in their food purchases (Fig. 3).

FDA has also suggested that acceptable hygiene practices, and cleaning and sanitization of kitchens’ and restaurants’ surfaces, are preferred precaution measures compared to the environmental monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 (FDA 2020). The personnel involved in the preparation and sale of food should be encouraged to adopt standard hygiene practices to control known foodborne viruses and bacteria. These include handling carefully raw animal products to avoid cross-contamination with other foods, washing vegetables and fruits before eating, cooking eggs or meat thoroughly, and covering nose and mouth when sneezing or coughing, among others (Safefood 2020). Since current evidence shows that individuals who are symptomatic comprise the most significant risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, food businesses should be following employee health recommendations and policies to keep covid positive individuals away from food processing (Seymour et al. 2020).

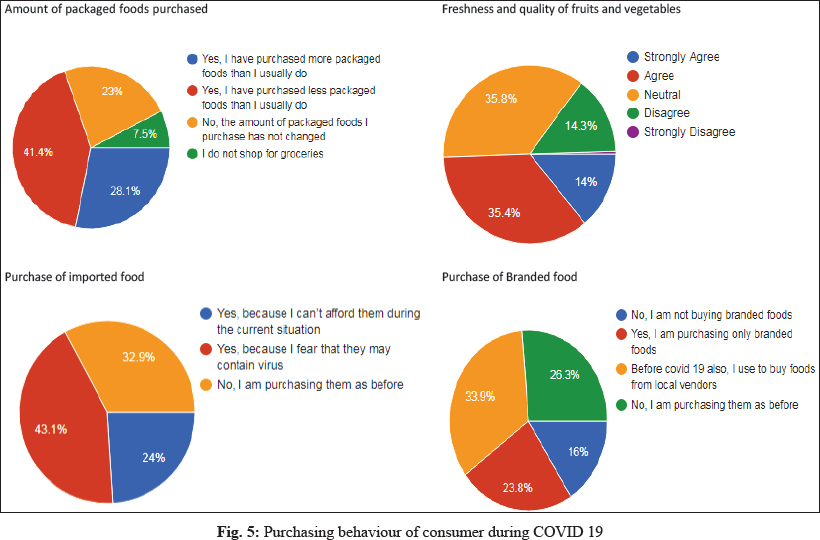

The responses about concern regarding food shopping during the last two months of the covid-19 lockdown period indicated that health of grocery stores employees (60.4%), the safety of food available (52.5%), the health of other shoppers (41.2%), and running out of fresh food stock were the topmost concerns. The responses about change in buying patterns regarding the purchase of packaged foods indicated that 41.4% of respondents purchased less packaged foods than usual; 28.1% of respondents purchased more packaged foods than expected and only 23% felt no change in the purchase of packaging foods. It was also noted that 37.6% of respondents had a very favorable opinion, 33.1% had a favorable view, and 29% felt there was no change in opinion on the healthfulness of the packaged foods (Fig. 4).

As food purchase is the main point of contact in everyday life of people during these days of the pandemic, the stores and vendors of food supply are mainly regarded as the source of inoculum in some cases (UNSCN 2020). After lockdown, food service businesses, as the last actor of the food supply chain, will have to operate again under pressure prioritizing the health of the workers in the sector and their outcomes (FAO 2020).

Among the responses on purchasing and preparation of foods during Covid-19, 45% of them felt that it was good to prepare food safely at home, 15.6% thought that it was good to shop safely for groceries in person, 15.1% thought that it was good to eat healthy food with a minimal budget. Only 9.6% felt that online purchases could be made, but safe receipt of them was to be taken care of. The demand for healthier diets, the supply of bioactive ingredients of foods and functional foods may increase as consumers are looking to guard themselves and their immunity system (Galanakis 2020). It was evident from our study that the respondents preferred safely prepared healthy food at home.

Among all the respondents, only 22.4% of them were very confident that the foods they purchased were safe to consume, while 48.2% felt that they were satisfied to some extent, but 20.4% of respondents thought that the food they bought,was not safe to consume. The respondents, when asked about the confidence in the ability of food manufacturers to supply enough food, to meet the customers’ requirements in the future, only 19% were very confident. Incomparison, 50.5% were somewhat confident and 22% of them were not convinced. A question about getting quality fruits and vegetables equivalent to pre-covid days was responded to with only 14% of them strongly agreeing and 35.4% moderately agreeing that they were sure of getting good quality fruits and vegetables. The remaining respondents were either neutral or disagreed, indicating that the respondents are not sure of getting quality foods during and after the covid crisis (Fig. 5).

During these Covid-19 days, supporting the immunity of the human body is top priority health goal worldwide. One among five shoppers listed immune system support as the prime motive for buying healthy products in a recent consumer survey. Right from the initial days of the Covid-19 pandemic, it's expected that buyers increasingly look for products to boost their immune system within the future (Galanakis 2020).

The total impact of the covid-19 pandemic on food sector is still not known as global concern until now is only on human health. However, the adverse consequences on food systems and people along the supply chain of food are already visible. To ensure food safety, and avoid any disruption of the food supply chain, it is essential to develop detection tools for SARS-CoV-2 that are applicable to foods. Trustworthy techniques of virus detection in food continues to be a challenge as the virus particles distribution is heterogeneous, the low viral load, and the non-optimal tedious isolation (Bosch et al. 2018).

The responses about purchasing branded foods indicated that 23.8% of respondents were purchasing only branded foods, while 33.9% were purchasing foods from local vendors, 16% were not buying any branded foods, while 26.3% were purchasing foods as before the covid crisis. This indicates that there is a major change in the purchasing pattern of foods during the covid crisis (Fig. 5).

Responses on a question regarding the purchase of foods from certain countries, 24% of them felt that they couldnot afford to purchase the imported foods as before, 43.1% feared that the imported foods might contain a virus, and 32.9% were buying them as early (Fig 5). Information gathered on changes in food purchase prices during the covid crisis indicated that 30.1% strongly agreed, and 40.4% agreed that there was a price hike. Only 8.3% felt that there was no price hike. The majority of the respondents felt an increase in the price hike.

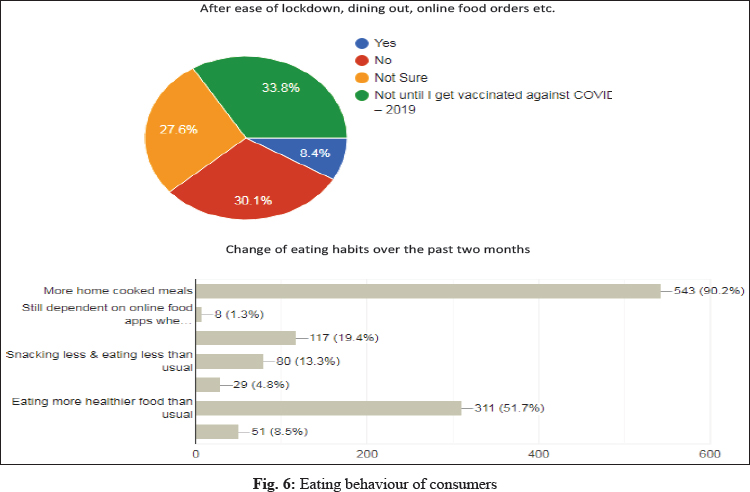

A change in eating habits was felt by most of the respondents during the two months of the covid -2019 lockdown period. 90.2% of respondents thought that they were consuming more home-cooked meals, 51.7% reported consuming healthier foods than pre covid days, indicating a massive impact on the eating pattern of the people who responded. While knowing about the eating habits among the consumers, 90.2% of the respondents consumed more home-cooked meals.

As it is a known fact that habits die hard, the respondents who experienced a change in consumption pattern, when asked about whether they would go back to their old habits of eating, dining out, online orders, etc. It was observed that majority of them (33.6%) did not want to go back to their old habits until they get vaccinated against covid. A mere 8.4% of respondents wanted to go back to their old habits, while 30.1% of respondents did not want to return to their old food habits, and 27.6% were not sure about changing their eating habits post covid crisis (Fig. 6). The rampant spread of the covid-19 lead to switching of food preferences by majority of people. Long-held food preferences are hard to change, but a quick change did happen during the covid-19 period concerning food purchases, behavior, and safety practices.

CONCLUSION

Many of the respondents were trying to manage the covid crisis with proper sanitization measures, social distancing, and wearing masks while purchasing foods. It was also observed that most respondents felt that the vendors are even wearing good personal protection accessories like masks, gloves, etc. The tidiness of retail space and employee and co-buyer hygiene are going to play a role in the selection of retails by consumers for some time to come. Wearing protective equipment, regular cleaning, providing sanitizers were acknowledged as necessary actions that grocery store employees can take about food safety. The health of other shoppers and grocery store employees, and running out of staple foods, were the most concerning parts of food shopping. Regarding the perception of food safety, it was found that most of the respondents were confident that the foods they purchased were safe to consume. However, not much-branded food purchase was found, rather food purchases were more from local vendors.

Purchasing and eating habits have changed. People were shopping less in-person and consuming more home-cooked meals while managing with existing stocks. More than half of the respondents also felt that they were consuming more healthy foods, as they were purchasing less packaged foods than usual. Regarding the new adapted eating habits, it was observed that most of the respondents did not want to go back to the old eating patterns. Most people are confident in the safety of the food supply and the ability of food producers to meet their needs. The results indicate that the current Covid-19 pandemic is all about very rapid change. Consumer behavior changed rapidly throughout, for the crisis. Food consumption, and eating habits, have been significantly impacted due to concerns about hygiene, personal safety, food purchases, and consumption.

Acknowledgments:

We thank the Professor Jayashankar Telangana State Agricultural University (PJTSAU), Hyderabad, Telangana, for the support received during the study period.

REFERENCES

Bogoch, Watts, A., Thomas-Bachli, A., Huber, C., Kraemer, M.U. and Khan, K. 2020. Pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: potential for international spread via commercial air travel. J. Travel Med., 272: 1–3.

Bosch, A., Gkogka, E., Le Guyader, F.S., Loisy-Hamon, F., Lee, A. and Van Lieshout, L. et al. 2018. Foodborne viruses: Detection, risk assessment and control options in food processing. Int. J. Food Microb., 285: 110–128.

Cobb, T.D. 2001. Reclaiming our food: how the grassroots food movement is changing the way we eat. Storey Publishing, Adams, MA, USA.

FAO COVID-19 and the risk to food supply chains: How to respond? IPolicy support and Governance! food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2020. http://www.fao.org/policy-support/resources/resources-details/en/c/1269383/ Accessed on 10 August 2020.

FDA. 2020. Best practices for retail food stores, restaurants, and food pick-up/delivery services during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-during-emergencies/best-practices-retail-food-stores-restaurants-and-food-pick-updelivery-services-during-covid-19. Accessed on 10 August 2020.

Galanakis, C.M. 2020. The food systems in the era of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic crisis. Foods. 9(4).

Gamage, S.D., Kravolic, S.M. and Roselle, G. 2009. Emerging infectious diseases: concepts in preparing for and responding to the next microbial threat. In: Koenig KL, Schultz CH, eds. Koenig and Schultz's Disaster Medicine: Comprehensive Principles and Practices. Cambridge University Press, pp. 75–102.

Pung, R., Chiew, C.J., Young, B.E., Chin, S., Chen, M.I.C. et al. 2020. Investigation of three clusters of COVID-19 in Singapore: Implications for surveillance and response measures. The Lancet, 395(10229): 1039–1046.

Reissman, D.B., Watson, P.J., Klomp, R.W., Tanielian, T.L. and Prior, S.D. 2006. Pandemic influenza preparedness: adaptive responses to an evolving challenge. J. Homel. Sec. Emerg. Manag., 3: 1–24.

Rizou, M., Galanakis, I.M., Aldawoud, T.M. and Galanakis, C.M. 2020. Safety of foods, food supply chain and environment within the COVID-19 pandemic. Trends Food Sci. Technol, 102: 293–299.

Safefood. 2020. COVID-19 advice - safe food. https://www. safefood.qld.gov.au/covid-19-advice/. Accessed on 15 July 2020.

Seymour, N., Yavelak, M., Christian, C. and Chapman, B. 2020. COVID-19 and food safety FAQ: Is corona virus a concern with takeout?. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fs349. Accessed on 15 July 2020.

UNSCN Food environments in the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. https://www.unscn.org/en/news-events/recent-news?idnews=2040 Accessed on 10 August 2020.

Zhu, N., Zhang, D., Wang, W., Li, X., Yang, B., Song, J. et al. 2020. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med., 382: 727–33.