International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Biotechnology

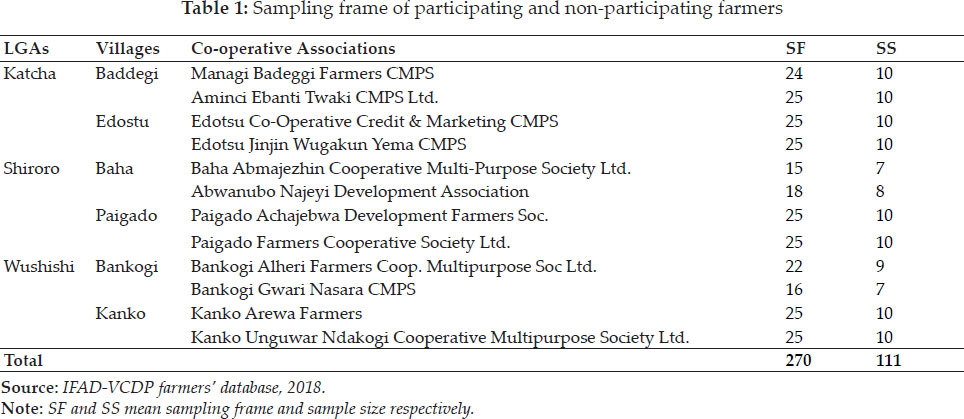

Citation:

DOI: 10.30954/0974-1712.03.2020.7

ENTOMOLOGY

Studies on the Effect of Different Types of Feeding on the Commercial Characters of Mulberry Silkworm (Bombyx mori L.) in West Bengal: A Review

ABSTRACT

The silkworm Bombyx mori is essentially monophagous and survives solely on the mulberry leaves (Morus spp.). Mulberry is a highly heterozygous and vegetatively propagated species that is prone to prolonged juvenile period. Since the quality of silk production is directly proportional to the quality of leaves used as the exclusive feed for these worms, leaf quality is of utmost importance in sericulture. The quality of leaves is reported to depend upon age of leaf on the shoot, succulency and nutrient content. The nutrient contents of mulberry leaves are known to vary according to the season, variety, age, type of harvesting. In addition, feeding with mixed varieties leaves and feeding frequencies are also known to influence the health of the silk worms. The present review paper discusses in details about the effects of different types of feeding on the commercial characteristics of mulberry silkworm (Bombyx mori L) in West Bengal.

Highlights

Choice of mulberry leaves suitable for healthy growth of mulberry silkworm is the vital factor in Sericulture Industry.

Choice of mulberry leaves suitable for healthy growth of mulberry silkworm is the vital factor in Sericulture Industry.

This paper discusses and reviews the effect of differential feeding on the commercial characters of Mulberry silkworm (Bombyx mori L) which helps to select appropriate technique of feeding during the course of silkworm rearing.

This paper discusses and reviews the effect of differential feeding on the commercial characters of Mulberry silkworm (Bombyx mori L) which helps to select appropriate technique of feeding during the course of silkworm rearing.

Keywords: Mulberry leaf, Silkworm, Feeding

Sericulture in India is an important agro-based cottage industry providing employment to millions in the villages and earning foreign exchange to the tune of 2000 crores of Rupees per year. Indian sericulture is largely dependent on mulberry silk production by the silkworm Bombyx mori L. The silkworm Bombyx mori is essentially monophagous and survives solely on the mulberry leaves (Morus spp.). Mulberry is a highly heterozygous and vegetatively propagated species that is prone to prolonged juvenile period. The cultivation of mulberry for raising silkworm cocoon should aim not only at increased production of leaves per unit area but also leaves of suitable quality for the maximum utilization of the leaf crop produced. The food quality relevant to all the aspects of insect performance including growth, development and reproductive potentialities depends mainly on nutritional composition. Bombyx mori L. feeds primarily on mulberry leaves and prefers leaves of different maturity viz. tender, medium and mature based on position in different stages of its larval period. Since the quality of silk production is directly proportional to the quality of leaves used as the exclusive feed for silkworms, leaf quality is of utmost importance in sericulture.

How to cite this article: Sarkar, K. (2020). Studies on the Effect of Different Types of Feeding on the Commercial Characters of Mulberry Silkworm (Bombyx mori L.) in West Bengal: A Review. IJAEB, 13(3): 305–321.

Source of Support: None; Conflict of Interest: None

The growth and development of silkworm larvae and economic characters of cocoons are influenced largely by the nutritional quality of mulberry leaves fed. Matsumara et al. (1958) reported that out of the various characters responsible for success of cocoon crop mulberry leaf stood first (38.2%) followed by climate (37%), rearing techniques (9.30%), silkworm race (4.02%), Silkworm eggs (3.10%) and other factors (9.60%) etc. Nearly 70% of the silk protein produced by the silkworm is directly derived from the protein of the mulberry leaves (Fukuda et al. 1959). Hence, choice of mulberry leaves suitable for healthy growth of silkworm is one of the important factors in sericulture. Mulberry leaves suitable as food for silkworms must contain several chemical constituents such as water (80%), protein (27%), carbohydrate (11%), minerals and vitamins and must have favourable physical features such as suitable tenderness, thickness, tightness etc. in order to render them acceptable by silkworms. (Rajan & Himanthara, 2005).

It is clear from the above that mulberry leaf is more viable than any other factor and rearing of silkworm requires specific stages of leaf. Though in tropical condition mulberry can be grown through out the year but quality of mulberry leaves are still not upto the merit particularly at farmers’ level. Quality of leaf is one of the major problems behind the problems of silkworm rearing in tropics (Suranayanan 1988; Noman 1988) and the poor quality of leaf is one of the important factors attributed to the poor productivity of silk per unit area (Nagarajan and Radha 1990).

The quality of mulberry leaf varies significantly with the factors such as soil fertility, agronomical practices, planting system, environmental condition (Bongale et al. 1991; Datta 1992). The quality of leaves is reported to depend upon age of leaf on the shoot, succulency and nutrient content (Krishnaswami 1986; Benchamin and Nagraj 1987). The nutrient contents of mulberry leaves are known to vary according to the season, variety, age type of harvesting (Krishnaswami 1978; Das and Vijyaraghavan 1990; Liaw et al. 1991; Sarkar et al. 1992 and Rajan and Himantharaj 2005). In addition, feeding with mixed varieties leaves and feeding frequencies are also known to influence the health of the silkworms (Machii and Katagiri 1990; Barman 1992).

In the earlier studies it has also been reported that the top tender leaves nutritionally richer compared to medium, matured and over matured leaves (Rangswami et al. 1976; Sinha et al. 1993 and Bongale et al. 1997) and having less density of pubescence with blunt tip (Trivedi et al. 2008). It has revealed that the incidence and spread of diseases can be minimized and the cocoon characters may improve if silkworm larvae were fed with 65 days old mature leaf (Vijaya Kumari et al. 2001).

Sericulture is practiced in West Bengal since centuries and it is an age old industry in West Bengal. It is the major traditional state of mulberry silk production in India. Estimated mulberry raw silk production during 2018–2019 was 2394 MT (6.74% of total mulberry raw silk production in India) [ministryoftextiles.gov.in). But Estimated mulberry raw silk production during 2004–2005 was 10.39% of total mulberry raw silk production in India (Giridhar and Sampath, Compendium of Statistics of Silk Industry, 1999 & 2003). There is lot of factors behind that downfall of sericulture in the state.

In West Bengal rearing is conducted mainly in dry summer and wet summer. November to April comes under dry summer which is considered as favourable season in West Bengal and May to part of October comes under wet summer which is considered as wet summer in West Bengal (Das et al. 1994, 2006; Sarkar et al. 2008, 2012; Sarkar and Majumdar 2016 and 2017).

It is true that it is not easier to rear productive bivoltine races or even crossbreeds during unfavourable season (May to part of October) because crossbreeds with bivoltine components cannot with stand high temperature and greater humidity (Murakami 1989; Tazima 1991; Das et al. 1994, 2006; Sarkar et al. 2008; Sarkar and Moorthy 2012). So, rearing of high yielding races in our State is not in the reach of farmers. But our farmers even do better by using traditional multivoltine hybrid (N×M12 (W) and cross breed N×NB4D2) if they can provide them exact quality or exact maturity level of leaves at right time. It is certain that the growth and development of silkworm larvae and economic characters of cocoon are influenced largely with maturity of leaves. But very less number of big and small farmers of West Bengal is aware of types of leaves to be fed to silkworm in different season in different instar (Chattopadhyay et al. 2004). Even feeding of proper maturity level of leaves at right time to silkworm larvae may reduce the adverse effect of climate on silkworm larvae. Practice of shoot feeding and feeding of highly water content tender leaves and even water treated leaves may help the farmers to harvest quality cocoon crop (Sekharappa et al. 1993; Mathur 1997; Vage and Ashoka 2000; Talebi et al. 2002; Rahamathulla et al. 2003; and Sarkar et al. 2008, 2012 and 2020).

In contrast some contradictory ideas are also there. In West Bengal at farmers’ level there is a trend to feed silkworm with medium to mature leaves by clipping the top tender leaves in late stages. There is a strong belief is working behind the activity. The belief is that tender leaf feeding during late age causes grasserie disease. Some authors also stated that feeding of tender leaves and water treated leaves induce grasserie disease in silkworm (Siva Prakasham 1996; Basarajappa and Savanurmath 1997 and Elumalai et al. 2001). But almost 20% tender leaves are found in a mulberry shoot of 6570 days. So by providing a mulberry shoot with tender leaves in the latter stages may also save 20% of leaves which have great economic value. Differential feeding has a great impact on different season of rearing.

Since silkworms do not drink water, they get their moisture from the leaves. So the supplied leaf must be fresh. Leaf quality often mainly implies leaf moisture content, thereby ignoring other nutritive components (Bongale et al. 1997; Friend 1958; and Waldbauer 1968). Several scientists have also reported highlighted the importance of dietary moisture content and reported importance of leaf moisture content in relation to the performance of silkworm (Narayana Prakash et al. 1985 and Paul et al. 1992). So, during dry summer when moisture comes too lower than the optimum, effect of tender leaf feeding and using of even water treated leaves may become significant to raise the humidity of rearing bed as well as moisture content of silkworm larvae. At the same way adoption of shoot rearing may also help to maintain proper moisture in the rearing bed because leaves remain fresh for a longer duration due to attachment with the twigs. Shoot rearing also can save labour, time, leaf, number of bed cleaning and rearing space in late stage and it also helps to maintain hygienic condition in the rearing bed (Sekharappa et al. 1993; Mathur 1997). But concept of shoot rearing is still not popular in West Bengal at farmers level (Chattopadhyay et al. 2004). Sarkar et al. (2020) suggested that during dry summer [November- April] shoot with tender leaves will be beneficial for the growth of silkworm. But in West Bengal there is a trend to feed shoot to silkworm by clipping the tender leaves in later stages. Almost 20 % tender leaves are found in a mulberry shoot of 65–70 days. So by providing a mulberry shoot with tender leaves in the latter stages not only help to enrich the commercial characteristics of cocoon but also saves 20% of leaves which have great economic value.

Even During the dry summer particularly in the month of February farmers of West Bengal face lot of problems in terms of availability of mulberry leaves in the mulberry garden. Growth of mulberry plant is also minimal at that period. So farmers may use succulent tender leaves of mulberry plant in huge quantities. Sarkar et al. (2008), Trivedi et al. (2008) suggested that tender leaf contains high moisture, immature and blunt tip of pubescence with high protein content. So it is more palatable to silkworm than other maturity level of leaves. Sarkar et al. 2008, 2012 suggested that the most of the larval and cocoon characters were recorded significantly higher in tender leaves fed batches followed by medium leaves fed batches. Performance of shoot feeding in late instar is also effective. According to him significantly higher post cocoon parameters viz. average filament length, nonbreakable filament length; renditta and raw silk recovery percentage etc. were recorded in tender leaf fed batches. Sarkar et al. 2008, 2012 also suggested that interms of qualitative analysis of leaf tender leaf is more nutritious than other maturity level of leaves. Sarkar et al. 2008, 2012, 2020 and Sarkar and Majumdar 2016 suggested that both in dry summer and wet summer performance of mature leaf and mature shoot fed batch was worst. Basu et al. (1995) also found that performance of mature leaf fed batch was least in terms of all the commercial characters of silkworm among different maturity level of leaves. Singh et al. (2006) suggested that certain physical factors in the environment are known to affect the physiology of the insects. According to them high temperature and high humidity plays an important role on insect and increase susceptibility to pathogens. Silkworms are also susceptible to viral infection like Bombyx mori Nuclear Poly Hedrosis Virus (NPV) with decrease or increase in temperature (25°C). They have also suggested that silkworm fed with mulberry containing low proteins, sucrose or high cellulose tends to more susceptible to viral infections.

But during wet summer when moisture goes above than the optimum, feeding of silkworm larvae with high moisture content leaves and even water treated leaves may become detrimental to the growth of silkworm larvae particularly in late stage when silkworm larvae require less moisture (Ueda 1982). It is also true that feeding silkworm larvae with completely dry leaves is also not possible during rainy season. Talebi et al. (2002) in Iran indicated that moisture contents can be increased more than 1% when fresh mulberry leaves dipped in water for 15 and 30 minutes respectively and as well as he mentioned improvement of all the traits when silkworms were fed with highly moisture content leaves. Sarkar et al. 2008, 2012 indicates that in case of feeding of water treated larvae to silkworm larvae, high moisture content leaf is suitable for silkworm larvae at dry summer but water in the surface of the leaf may be harmful for silk worm larvae. So, it is important to feed silkworm larvae by just shaking the water from surface of the leaf or dry the leaves for few minutes. The study also reveals that if wet leaves are dried for some time, it helps to increase the moisture percentage of leaves. It is also helpful to improve the cocoon characters.

Sarkar et al. (2015) suggested that there is no negative effect of using Amaranthus spp. as intercrop of mulberry on the quality of mulberry leaf. Sarkar et al. (2018) also suggested that the development and reproduction of insects are greatly influenced by a variety of nutritional and climatic factors. These factors may exert their effects on insects either directly or indirectly. Under natural conditions organisms are subjected to a combination of nutritional and climatic factors, and it is this combination that ultimately determines the distribution and abundance of a species. This paper discusses and reviews the effect of differential feeding on the commercial characters of Mulberry silkworm (Bombyx mori L) which helps to select appropriate technique of feeding during the course of silkworm rearing.

Differential Feeding Technique in West Bengal

West Bengal is the major traditional silk producing state of India. It is the third largest silk producing state of our country. In West Bengal rearing season is divided mainly in two parts i.e. dry summer and wet summer. November to April comes under dry summer (except a very brief period of winter) where temperature is higher than optimum and humidity is lower than optimum. May to October comes under wet summer where temperature and humidity both are higher than environment. Mulberry is the sole food plant of Bombyx mori. Mulberry crop span is 70 days. So five leaf harvests as well as five rearings of silkworm are done in a year. November crop (winter or Agrahani), February crop (spring or Falguni) and April crop (summer or Baishaki) come under dry summer where June-July crop (Rainy or Shrabani) and August-September crop (autumn or Aswina) come under wet summer (Das et al. 1994, 2006; Sarkar et al. 2008, 2012; Sarkar and Majumdar 2016 and 2017).

Differential Feeding Technique in Dry Summer

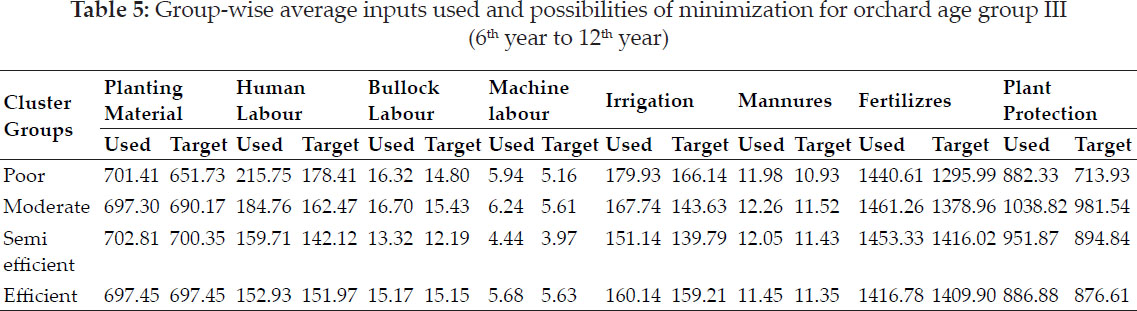

The silkworm Bombyx mori is essentially monophagous and survives solely on the mulberry leaves (Morus spp.). Mulberry is a highly heterozygous and vegetatively propagated species that is prone to prolonged juvenile period. Since the quality of silk production is directly proportional to the quality of leaves used as the exclusive feed for these worms, leaf quality is of utmost importance in sericulture. Sarkar et al. (2008) suggested that in S-1635 mulberry variety which considers as ruling mulberry variety in West Bengal tender leaves contained 79.59% leaf moisture, 82.41% moisture retentions capacity after 6 hours, 49.78 mg/gm of total soluble sugar and 30.82 mg/gm of total soluble protein followed by medium leaf which contained 72.92% leaf moisture, 74.91% moisture retentions capacity after 6 hours, 47.22 mg/gm of total soluble sugar and 28.67 mg/gm of total soluble protein. Mature leaf contained 67.13% leaf moisture, 70.02% moisture retentions capacity after 6 hours, 45.34 mg/ gm of total soluble sugar and 27.63 mg/gm of total soluble protein respectively (Table 1). This study suggested that tender leaf is more nutritious than other maturity level of leaves. The nutrient quality of mature leaf is very poor. This observation is almost similar to the observations laid by Rangswamy et al (1976), Bongale et al. (1991) and Patil (2002). According to them the top tender leaves are nutritionally richer compared to medium, matured and over matured leaves. They also reported that the maximum values of leaf moisture, protein, sugar contents and moisture were recorded with tender leaves, which gradually depleted at varied degrees with increasing maturity levels among the varieties. It is well known fact that silkworm cannot drink water separately; it takes water only from leaf. On the other hand protein is important because it helps in synthesis of silk and helps in production of silkworm eggs. Carbohydrate acts as a source of energy in Silkworm and it also helps in synthesis of fats. So, feeding of tender leaves to silkworm larvae assumes greater importance. But in tropical and subtropical belt of India particularly in West Bengal at farmers’ level there is a trend to feed silkworm with medium to mature leaves by clipping the top tender leaves particularly in late stages. There is a strong belief is working behind the activity. The belief is that tender leaf feeding during late age causes grasserie disease. Even same belief was also reported from some certain scientists (Sivaprakasham (1996) Basarajappa and Savanurmath (1997) Elumalai et al. (2001)) but Sarkar et al. 2008 and 2012 clearly proved that there is no relation between tender leaf feeding and occurrence of grasserie disease. He also suggests that tender leaf fed batch showed highest effective rate of rearing and lowest melting percentage particularly in dry summer in West Bengal. Actually the main reason behind the occurrence of grasserie disease is not clear till date. Kawakami, K (2001) suggested that high (28-35°C), low (10-20°C) temperature and humidity (below 70%) as well as drastic changes in temperature and humidity during the rearing may cause grasserie disease in silkworm. On the other hand Nataraju et al. (2005) suggested that silkworm Bombyx mori appears normal and shows no symptoms or change in appetite during more than two third of incubation period in case of grasserie disease of silkworm (Caused by Bombyx mori nuclear polyhedrosis virus). He also suggested that the signs and symptoms caused by the nuclear polyhedrosis virus in general are not apparent for several days. Usually the first symptoms appear 5–7 days post infection. But in the present investigation author found grasserie infected larvae even in 1st instar itself. So, who knows grasserie may occur due to transovarial transmission? Sarkar et al. (2008) clearly suggested that November to April when humidity is relatively lower in the environment, it is better to feed silkworm with succulent tender leaves. Tender leaves contain more moisture, more soluble sugar, more soluble protein and having more moisture retentions capacity will be helpful for silkworm rearing to maintain more moisture in the rearing bed. Sarkar et al. (2012) again suggested that tender leaf fed batch significantly showed better performance in respect of all the characters, he suggested that profuse use of tender leaves during dry summer increased the cocoon yield/100 DFLs (55.72 kg) significantly than control batch (47.26 kg) for the cross breed N>NB4D2 (Table 2). As a whole the study results concluded that filament length could be increased if the worms are fed with the leaves of good moisture and protein content (Table 3). Sarkar et al. (2012) also suggested that when silkworm was fed with tender leaves throughout larval stages and only during late larval stage during November, February and April, it showed high effective rate of rearing and less melting percentage (Table 2). It clearly indicates that there is no relation behind tender leaf feeding and occurrence of grasserie in silkworm larvae. On the other hand tender leaf fed batch showed least percentage of gattine (swalpa) infected larvae in the rearing bed during November, February and April. Tender leaf fed batch also showed least larval duration in 5th instar (Table 2). This indicates that leaf consumption is comparatively less in tender leaf fed batch. Because during fifth instar silkworm larvae almost consume 80% of total leaves. So, any less in the duration of 5th instar directly help to curtail the total leaf requirement. This result is supported by the findings of Narayanan, 1967 Basu et al. (1995), Raja Shekhar gouda and Laksmikanth (1998), Vage and Ashoka (2000) and Rahamathulla (2003). It is true that it is not possible to provide huge amount of tender leaves in late instar. But efforts should be taken to irrigate mulberry land frequently to keep maximum moisture in the mulberry leaves. Sarkar et al. (2020) indicates that during dry summer [November- April] shoot with tender leaves will be beneficial for the growth of silkworm (Table 4 and 5). But in West Bengal there is a trend to feed silkworm larvae with shoot by clipping the tender leaves from the shoot. There is a strong belief is working behind the activity. The belief is that tender leaf feeding during late age causes grasserie disease (Sivaprakasham (1996) Basarajappa and Savanurmath (1997) Elumalai et al. (2001)). But the present investigation clearly proved that in dry summer feeding silkworm larvae with tender shoot improved the commercial characteristics of cocoon. Almost 20 % tender leaves are found in a mulberry shoot of 65–70 days. So by providing a mulberry shoot with tender leaves in the latter stages not only help to enrich the commercial characteristics of cocoon but also saves 20% of leaves which have great economic value. It is normal practice at farmers level to feed silkworm with shoot consisted of mature leaves which is inferior in terms of all nutritional characters (Rangswamy et al. (1976), Bongale et al. (1991) and Patil (2002)). But Sarkar et al (2020) clearly indicates that performance of matured shoot fed batch is worst (Table 4 and 5).

Performance of tender, medium and mix shoot fed batch and normal shoot feeding during November to April in late instar was better than conventional leaf feeding suggested that shoot feeding is always beneficial than individual leaf feeding particularly in later stage. He has also suggested that almost double man days are required in individual leaf feeding as compared to shoot fed batch (Table 6). Sarkar, 2020 also reported that If we analyze comparative economics between individual leaf fed batch and shoot fed batch, we can see an around ? (13200-7500) = 5700/ can be saved to rear 100 dfls silkworm in normal shoot feeding as compared to individual leaf feeding in terms of utilization of labour (Table 6). This observation is similar to observation laid by Mathur (1997). He suggested that a total of 27 man days can be saved for 100 DFLs rearing and approximately 54.86% cost on cocoon production can be reduced by adopting shoot feeding method. Sarkar, 2020, Sarkar and Majumdar 2016 also suggested that in case of shoot feeding silkworm larvae crawl on shoot one above another and in this way they can get rid from diseased larvae, litter, waste leaves etc. In this way shoot rearing also helps to maintain hygienic condition in the rearing bed. But Chattopadhyay et al. (2004) suggested that proper concept of shoot rearing is completely absent at farmers level in the three traditional district. So it is important to adopt shoot rearing technique at farmers’ level in West Bengal. For proper conducting of shoot rearing it is important to adopt three tier system of shoot rearing at farmers’ level. Present investigation clearly indicates that shoot rearing is highly advantageous to get good cocoon crop at farmers’ level. So it definitely helps for sustainable development in Sericulture Industry. Sarkar et al. (2012) also suggests Feeding larvae with leaves which were water dipped and dried for entire larval instar and feeding larvae with leaves which were water dipped and dried in late larval instar showed significantly better performance than conventional leaf feeding method in dry season. It clearly suggested that high moisture in leaf significantly improve quantitative character of cocoons (Table 7 and 8). This observation is also similar to the observation laid by Naryanprakash et al. (1985) who reported that assimilated food converted into body tissue and conversion efficiency decreased with decreasing dietary moisture content in mulberry leaves and also shell weight and fibroin content of the cocoons increased with increasing dietary moisture. Paul et al. (1992) also reported that absolute consumption and growth rate per day per larva, the quantity of dry matter consumed and digested, the values of efficiency of conversion of ingested and digested food and final larval weight increased with increasing percentage of leaf water and approximate digestibility increased progressively upto 70% leaf moisture but was reduced at the control dietary water level (76.6% leaf moisture). It was found that when the leaves were water dipped for 15–20 minutes its moisture percentage was increased even upto 2–3%. In West Bengal dry summer is very important in relation to rearing point of view because particularly November and February crop are considered as best crops for silkworm rearing in West Bengal ((Das et al. 1994, 2006; Sarkar et al. 2008, 2012; Sarkar and Majumdar 2016 and 2017). It is due to prevailing of comparatively lower temperature in the environment during that time in West Bengal as we know exposing of high temperature particularly during 4th and 5th instars are harmful for silkworm rearing (Ueda et al. 1962; Shirota 1992; Tazima and Ohuma 1995). But due to less rainfall, comparatively low humidity in rearing room as well as in rearing bed are prevailing in November and February crop in West Bengal. To overcome this problem it is important to feed silkworm larvae with profuse amount of tender leaves. Sarkar et al. (2006) and Trivedi et al. (2008) also suggested that due to presence of immature and blunt type of pubescence, tender leaves are more favourable and palatable for silkworm larvae. It is true that it is not possible to provide huge amount of tender leaves particularly in late instar. But efforts should be taken to irrigate mulberry land frequently to keep maximum moisture in the mulberry leaves.

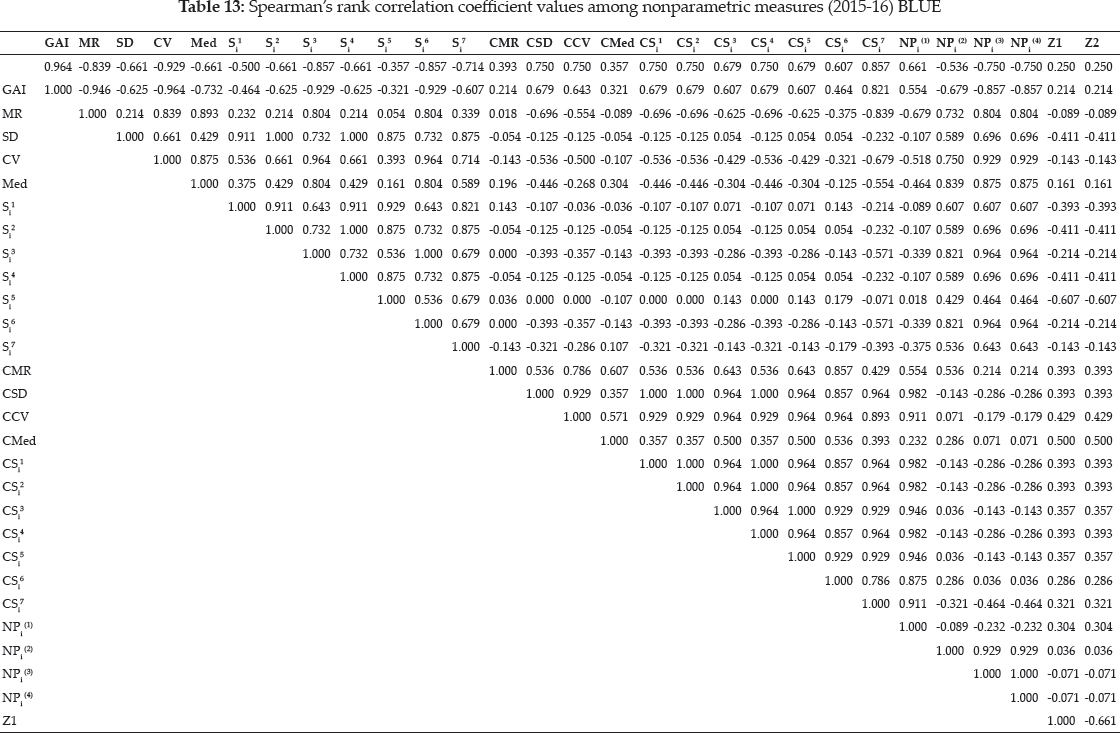

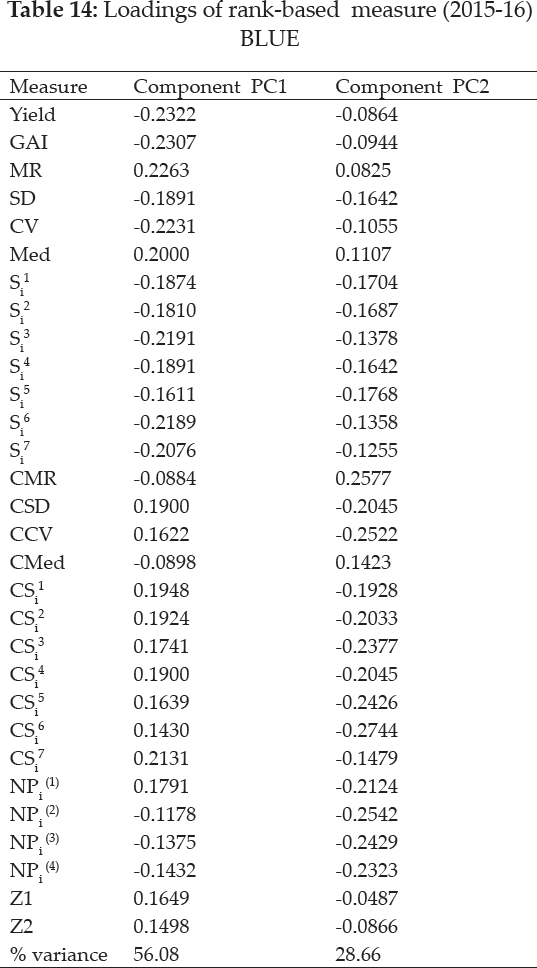

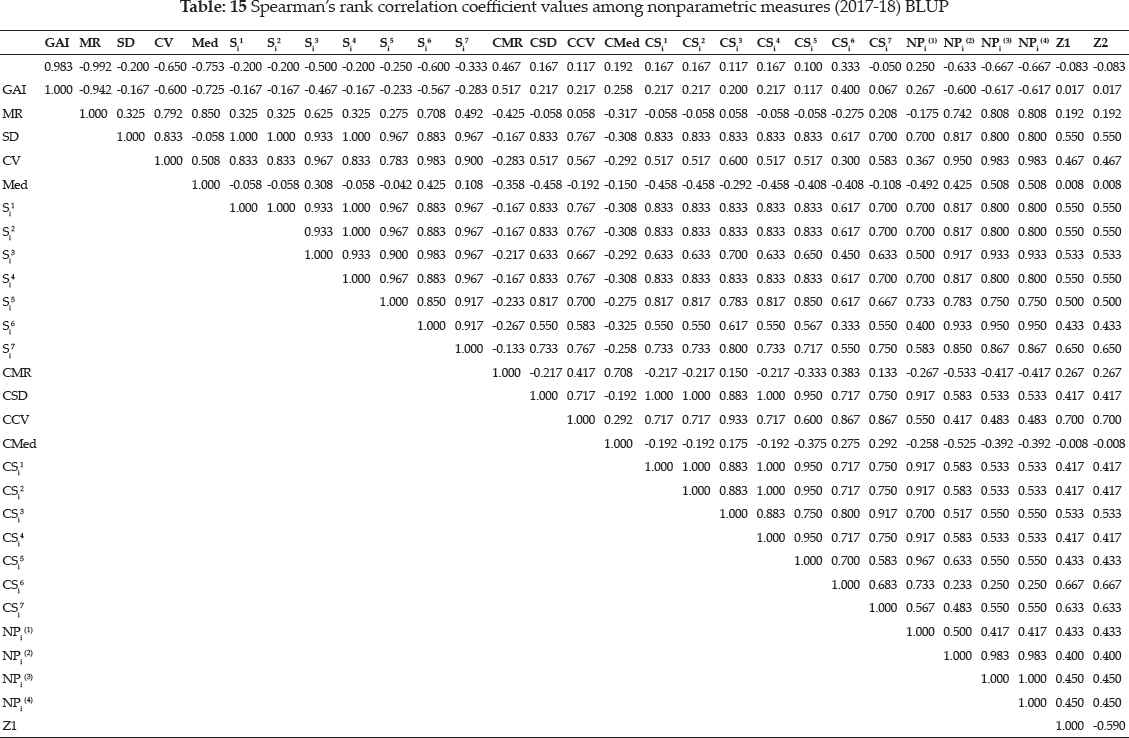

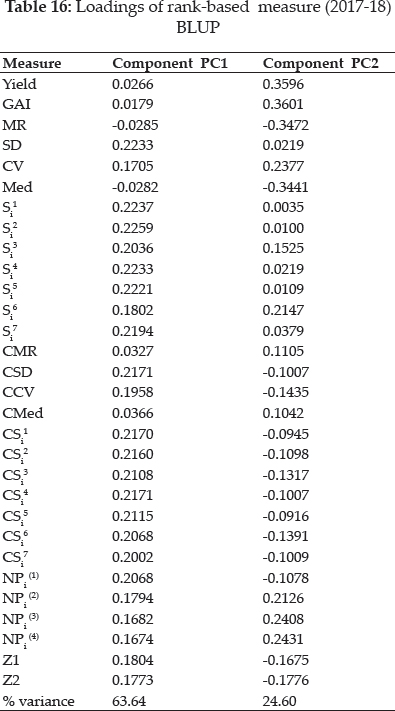

Differential Feeding Technique in Wet Summer

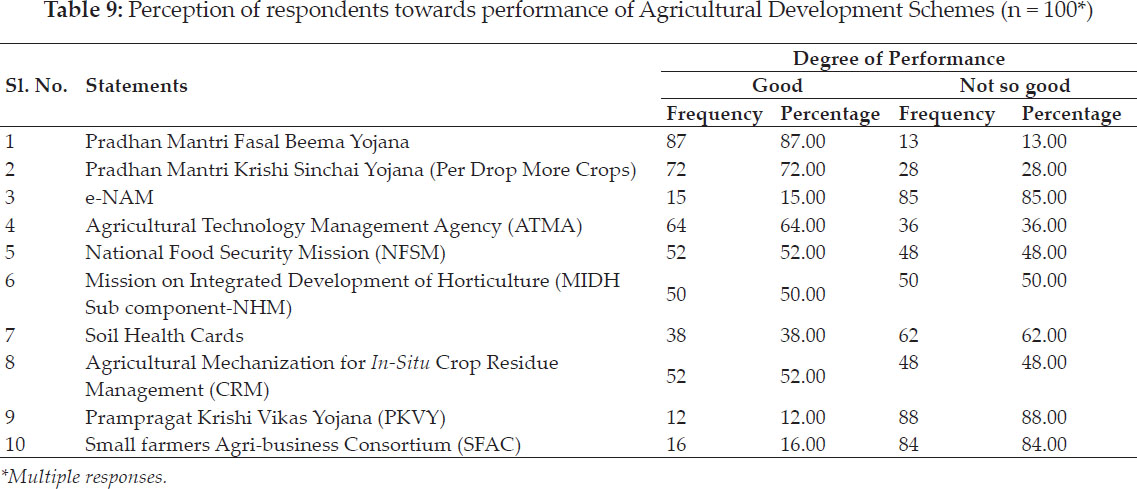

But reverse trend is usually seen in wet summer where feeding silkworm larvae with tender leaves, tender shoots and with water treated leaves in late age become detrimental to silkworm larvae (Table 9–14). Ueda, 1982 indicated that during late instars silkworms started to release water and 50% of released water used in solidification of silk. According to him 4th and 5th instar of silkworm larvae considered as stage of water releasing. He also reported during spinning a great amount of water is discharged. Amount of water released during 3 days before the end of silk spinning is 46 liter by 20,000 larvae (7.8 liter for urination, 4.5 liter in the form of fecal matter, 10.7 litre through respiration and 23 liter for silk solidification) so in wet summer where humidity is usually higher in the rearing room, it is important to feed silkworm larvae with medium to mature leaves (Table 9 and 10) which contains comparatively less moisture and it is also necessary to maintain comparatively less humidity in the rearing room and as well as in mounting room. This may also considered as combined effect of nutritional as well as climatic factors (Bhattacharyya et al. 2017; Sarkar et al. 2018). But November to April (dry summer) and June to September (wet summer) performance of mature leaf and mature shoot fed batch was worst (Table 2 & 3, Table 4&5, Table 9 & 10 and Table 11 & 12). Sarkar et al. (2020) suggested that performances of exclusive tender shoot feeding and mature shoot feeding are not beneficial to silkworm larvae in wet summer) which also affects performances of mixed shoot fed batch where tender and mature shoots are given separately (Table 11 & 12). But in case of normal shoot feeding due to presence of all types of leaves i.e., tender, medium and mature provides a balanced diet to silkworm larvae in wet summer and yields better results (Table 11–12). Sarkar et al. 2008; Sarkar et al. 2020 suggested that during wet summer (May to October) it is better to feed silkworm with medium leaf, medium shoot and even feeding silkworm larvae with normal shoot may also helpful for sericultural farmers. But in both in dry summer and wet summer performance of mature leaf and mature shoot fed batch was worst. So matured and over matured garden can be regarded as the worst garden in terms of quality point of view. In wet summer there is always probability of wetting of mulberry leaves due to heavy rain, in this case Sarkar et al. (2008) suggested that to feed silkworm larvae by just shaking the water from surface of the leaves or by drying the leaves for few minutes. He also suggested that during June to September (wet summer) feeding larvae with leaves which were water dipped and dried for entire larval instar and feeding larvae with leaves which were water dipped and dried in late larval instar gave better result than control (Table 13 and 14). It indicates that even in rainy season farmers can provide wet leaves to silkworm by shaking the water from the surface of the leaves. In both dry summer and wet summer feeding larvae with immediately water dipped leaves in early instar gave good result (Table 7 & 8 and Table 13 & 14). This indicated that during early stage feeding of leaves even with water in surface cannot cause any harm to silkworm. Feeding larvae with leaves immediately water dipped for entire larval instar and feeding larvae with immediately water dipped leaves in late larval instar showed inferior results in terms of all commercial characters in both dry summer and wet summer (Table 7 & 8 and Table 13 & 14). Sarkar et al. (2011) suggested that double feeding is highly useful in wet summer. The main reason is that during wet summer in West Bengal comparatively higher humidity is available. So two feeding/day becomes sufficient. It also helps to make rearing tray hygienic. Generation of waste material during latter stages can also be easily handled due to less number of feeding. Besides that due to less entry of persons in the rearing room, chances of contamination also become less. Double feeding is highly economic interms of management of labour and other rearing operations. It also helps to reduce the cost of rearing operations. It is estimated that almost 50% curtle in labour is possible through double feeding method than normal four feeding/day method. He also stated that except larval duration not even a single character varies significantly when silkworm larvae are fed with two feedings instead of four feedings in wet summer (Table 15 & 16). Larval duration is slightly higher in case of double feeding method than other treatments (Table 15 & 16). Sarkar et al. 2008; Sarkar and Moorthy 2012; Sarkar et al. 2018 and 2020 suggested that, it is very difficult to rear silkworm larvae due to prevailing of both high temperature and high humidity in West Bengal during wet summer so this is usually considered as unfavourable season for silkworm rearing in West Bengal. Generally if humidity is increased by 4 %, temperature is decreased by 1degree centigrade but in West Bengal during wet summer both high temperature and high humidity are prevailing which is completely adverse for silkworm rearing (Ueda et al. 1962; Shirota 1992; Tazima and Ohuma 1995). Besides that due to high rainfall, fluctuation of temperature is also happening during this time which is also harmful for silkworm rearing. But in contrast, due to sufficient rainfall luxuriant growth of mulberry leaves is found during wet summer in west Bengal. So, proper feeding technique should be followed to curtail extreme climatic condition upto some extent during wet summer and help the farmers to ensure the proper utilization of mulberry leaves.

FUTURE STRATEGY

But both in dry summer and wet summer whatever the conditions newly hatched larvae should fed with tender leaves. Because Ueda (1982) again reported that newly hatched larvae content only 72% moisture but within II instar water content of the body rises up to more than 80%. So, it is very important to feed chawki worms with very high moisture content mulberry leaves. Only feeding of high moisture content leaves can help chawki worms to raise its body water content from 72% to 80% or above. High moisture in the body help chawki worms to digest the food. Besides that When silkworm larvae may be fed with tender leaves even during late larval stage during dry summer (November, February and April crop). There is no relation behind tender leaf feeding and occurrence of grasserie in silkworm larvae, it may be helpful to feed silkworm larvae with tender leaf in dry summer because it reduced the occurrence of gattine (swalpa) infected larvae in the rearing bed during November, February and April crop which is generally happened due to feeding of dry leaves to silkworm larvae. Tender leaf feeding also reduce the larval duration in 5th instar. This indicates that leaf consumption is comparatively less in tender leaf fed batch. Because during fifth instar silkworm larvae almost consume 80% of total leaves. So any less in the duration of 5th instar directly help to curtail the total leaf requirement. This study also revealed that by using tender leaf we can save 20 % of tender leaves in late instar particularly in dry summer which is generally clipped by Sericultural farmers of tropical and subtropical belt of India as well as in West Bengal in late larval instar before providing mulberry shoots to silkworm larvae. Advocating of shoot rearing also saves labour, time, leaf, number of bed cleaning and rearing space in late stage so it definitely helps for sustainable development in Sericulture Industry. Present study also indicates that double feeding is highly useful in wet summer. Double feeding is highly economic in terms of management of labour and other rearing operations. In rainfed Zone where leaf yield of mulberry is comparatively less and comparatively higher spacing is maintained between mulberry plants, (Setua 2006) marginal and sub marginal farmers can advocate the technique of intercropping (growing of two or more crops simultaneously on the same area of land for increasing the returns per unit area of land) to make Sericulture more remunerative. Sarkar et al. (2015) suggested that there is no negative effect of using Amaranthus spp. as intercrop of mulberry on the quality of mulberry leaf. Bioassay indicated that mulberry leaves harvested from the plots where mulberry was grown with Amaranthus spp. did not affect the growth of silkworm larvae and yield of cocoon significantly and it was possible to earn an excess of ? 4700 in one ha of land without affecting the quality of leaves and as well as health of silkworm larvae. The study also indicated that intercropping of mulberry with Cajanus cajan increased the fertility of soil and could generate an income of ₹ 20000/ha/year without affecting the leaf yield and larval health. Varshney (1985), Gurunadaha Rao (1986), Satapathy et al. (1987) also reported that intercropping of mulberry with various leguminous crop not only increase the income but also increase the fertility status of soil as well as nutritional quality of mulberry leaves. November is the best season for crossbreed rearing in West Bengal due to prevailing of comparatively lower temperature in the environment but for crossbreed rearing in November, it is important to prepare seed crop of its bivoltine component in September, but due to climatic disadvantages it is not possible to rear bivoltine seed crop in September in most part of West Bengal, it is the major disadvantages of sericulture in West Bengal (Chattopadhyay and Sarkar 2006 and 2008). So it is important to develop bivoltine seed zone in West Bengal to ensure supply of bivoltine seed cocoon throughout the year. Mulberry leaf is the sole food material of silkworm Bombyx mori L. Though in West Bengal mulberry can be grown throughout the year and soil of West Bengal also favours growth of mulberry but farmers are reluctant to maintain proper planting technique, proper spacing, proper application schedule of manures, fertilizers, water etc (Sarkar et al. 2018). So it is important to improve the quality of mulberry leaves by adopting proper measures. In dry summer when growth of mulberry plant is limited, frequent irrigation is necessary to maintain proper moisture in the mulberry field which ultimately helps to produce profuse quantity of mulberry leaves with high moisture content which are essential for silkworm rearing in dry summer. During wet summer due to sufficient rainfall luxuriant growth of mulberry leaves is found in west Bengal but due to high rainfall, fluctuation of temperature is also happening during this time which is also harmful for silkworm rearing. So, proper feeding technique should be followed during that time to curtail extreme climatic condition upto some extent and help the farmers to ensure the proper utilization of mulberry leaves.

REFERENCES

Barman A.C. 1992. Manifestation of bacterial and viral diseases of Silkworm Bombyx mori L. Role of mulberry leaves, Spacing and feeding frequencies in relation to atmospheric high temperature and humidity. Bull. Seri C. Res., 3: 46–50.

Basarajappa, S. and Savanurmath, C.J. 1997. Effect of feeding of mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves of variable maturity on the economics characters in some breeds of silkworm, Bombyx mori L. Bull. Seri. Res., 8: 13–17.

Basu, R., Roychaudary, N., Shamsuddin, M., Sen, S.K. and Sinha, S.S. 1995. Effect of leaf quality on rearing and reproductive potentiality of Bombyx mori L. Indian Silk, 33: 21–23.

Benchamin, K.V. and. Jolly, M.S. 1986. Principles of silkworm rearing; in Proceeding of Seminar on Problems and Prospects of Sericulture. Mahalingam. S. (ed.). 63–108. Vellore, India.

Benchamin, K.V. and Nagraj, C.S. 1987. Silkworm rearing techniques (Appr. Seri Tech. Jolly, M.S Ed.), pp. 64–106.

Bhattacharyya, B., Bhattacharyya, A., Majumdar, M. and Sarkar, K. 2017. Survey on flora and fauna of Bishnupur bill (horse shoe lake) and it’s surrounded area at Berhampore in Murshidabad district of West Bengal. International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Biotechnology, 10(5): 539–551.

Bongale, U.D., Chaluvachari, M. and Narahari Rao, B.V. 1991. Mulberry leaf quality evaluation and its importance. Indian Silk, 30: 51–53.

Bongale, U.D., Chaluvachari, M., Mallikarjunappa, R.S., Narhari., B.V., Anantharaman, M.N. and Dandin, S.B. 1997. Leaf nutritive quality associated with maturity levels in fourteen important varieties of Mulberry (Morus Spp) Sericologia, 37(1): 71–81.

Chattopadhyay, S.K., Sarkar, K. and Bhattacharya, D. 2004. Key Points behind the Success of Cocoon Crops at Farmers Level in West Bengal. Dissertation. University of Kalyani.

Chattopadhyay, S.K. and Sarkar, K. 2006. A Manual of Practical Sericulture (Vol-1).

Chattopadhyay, S.K. and Sarkar, K. 2008. A profile of sericulture. Journal of Environment and Sociobiology, 5(1): 1-6.

Das, P.K. and Vijyaraghavan. 1990. Studies on the effect of mulberry varieties and seasons on the larval development and Cocoon characters of silkworm Bombyx mori L. Indian J. Seric., 29: 19.

Das, S.K., Pattnaik, S., Ghosh, B., Singh, T., Nair, B.P., Sen, S.K. and Subba Rao, G. 1994. Heterosis analysis in some three way crosses of Bombyx mori L., Sericologia, 34(1): 51–61.

Das, S.K., Chattopadhyay, G.K., Moorthy, S.M., Verma, A.K., Ghosh, B., Rao, P.R.T., Segupta, A.K. and Sarkar, A. 2006. Silkworm Breeds and Hybrids for Eastern Region. In: Appropriate Technology in Mulberry Sericulture for Eastern and North Eastern India (17th and 18th January, 2006) workshop organized by C.S.R. & T.I., Berhampore: 91-96.

Datta, R.K. 1992. Guidelines for bivoltine silkworm rearing. Central Silk Board, Bangalore, India, pp. 18.

Elumalai, K., Ekambaram, E., Rajalakshmi, S., Sundaram, D., Raja, N., Jaykumar, M. and Jeyasankar, A. 2001. Influence of age of mulberry (Morus alba) leaves on economic traits of silkworm, Bombyx mori L. Uttar Pradesh J. Zool., 21: 159-161.

Friend, W.G. 1958. Nutritional requirements of Phytophagus Insects, Ann. Rev. Entomol., 3: 57–73.

Fukuda, T., Sudo, M., Matuda, M., Hayashi, T., Kurose, T. and Horiuhi M.F. 1959. Formation of silk Protein during the growth of the silkworm larvae, Bombyx mori L. In proceedings of the 4th instar. Cong. Bio-Chemistry, 12: 90-112.

Giridhar, K. and Sampath, J. 1999. Compendium of Statistics of Silk Industry. Published by Central Silk Board.

Giridhar, K. and Ramesha, M.N. 2003. Compendium of Statistics of Silk Industry. Published by Central Silk Board.

Gurundaha Rao, Y. 1986. Intercropping setaria with arhar. Indian Farming, 36(1): 8–9.

Kawakami, K. 2001. Illustrated working process of new bivoltine rearing technology.

Krishnaswami, S. 1978. New technology of Silkworm rearing. CSR&TI, Mysore. 1–10.

Krishnaswami, S. 1986. Mulberry cultivation in South India. CSB publication. Bangalore. 1–10.

Liaw, G.J., Hsieh, F.K. and Chu, Y-1 1991. Effectiveness of artificial diets prepeared from different varieties and maturity leaves on development of Silkworm Bombyx mori L., China J. Entomol., 11: 260–263.

Machii, H. and Katagiri, K. 1990. Varietal differences in food value of mulberry leaves with special reference to production efficiency of the cocoon shell. J. Seric. Sci. Japan, 59.

Mathur, V.B. 1997. Shoot rearing to save cost. The Indian Textile Journal, 80.

Matsumara, S., Tanaka, S., Kosaka and Suzuki, S. 1958. Relation of rearing condition to the ingestion and digestion of mulberry leaves in the silkworm, Sanshi. Shikenjo Hokokon Tech. Bull., 73: 1–40.

Ministry of textiles.gov.in. 2019. Functioning of Central Silk Board and Performance of Indian Silk Industry.

Murakami, A. 1989. Genetic studieson tropical races of Silk Worm (Bombyx mori) with special reference to cross breeding strategy between tropical races. JARO, 23: 123127.

Nagarajan, P. and Radha, N.V. 1990. Supplementation of amino acids through mulberry leaf for increased silk production. Indian Silk, 29(4): 21–22.

Narayanprakash, R., Periaswamy, K. and Radhakrishnan, S. 1985. Effect of dietary water content on food utilization on silk production in Bombyx mori L., Indian J. Seric., 24(1): 12–17.

Narayanan, E.S., Kasivishanathan, K. and Iyenger, M.N.S. 1967. Preliminary observations on the effect of feeding leaves of varying maturity on the larval development and cocoon characters Bombyx mori. Indian J. Seric., 1: 109–113.

Nataraju, B., Satyaprasad, K., Manjunath, D. and Aswani Kumar, C. 2005. A text book on silkworm crop protection. Published by Central Silk Board, pp. 99–100.

Nomani, M.K.R. 1988. Problems of Silkworm Rearing in Tropics, proceedings of the International Congress on Tropical Sericulture Practices, February 18–23, Central Silk Board, pp. 105–108.

Patil, V. and Santoshagouda 2002. Evaluation of promosing genotype, S1635 under irrigated condition of southern India. Indian J. Seric, 41(2): 160–161.

Paul, D.C., Rao, G.S. and Deb, D.C. 1992. Impact of dietary moisture on nutritional indices growth of Bombyx mori L. and concomitant larval duration. Journal of Insect Physiology, 38(3): 229–235. 203.

Rahamathulla, V.K., Raj, T., Himanthraj, M.T., Vindya, G.S. and Geetha Devi, R.G. 2003. Effect of feeding different maturity leaves and intermixing of the leaves on the commercial characters of Bivoltine Hybrid Silkworm (Bombyx mori L.), International Journal of Industrial Entomology, 6: No.1: 15–19.

Rajan, R.K. and Himantharaj, M.T. 2005. A Text Book on Silkworm Rearing Technology. Published by Central Silk Board.

Rajashekharagouda and Laxmikant. 1998. Effect of feeding tender leaf on economic traits of Bombyx mori L. Third National seminar on prospects and problems of sericulture in India. March, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, pp. 16–18.

Rangswami, S., Narasimhanna, M.N., Kasiviswanthan, K., Sastry, C.R. and Jolly, M.S. 1976. Sericulture Manual- I Mulberry cultivation. FAO Agricultural Services, Bulletin, 15/1, Rome, 150.

Sarkar, A.A., Qader, M.A. and Ahmed, S.U. 1992. Studies on the nutrient composition of some indigenous and exotic mulberry varieties. Bull. Seric. Res., 3: 8–13.

Sarkar, K., Bhattacharya, D.K. and Chattopadhyay, S.K. 2008. Studies on the effect of differential feeding on the commercial characteristics of Mulberry Silkworm (Bombyx mori L). Ph.D thesis, University of Kalyani.

Sarkar, K., Bhattacharya, D.K, Chattopadhyay, S.K, Trivedi, S. and Ghoshal, S. 2008. Effect of feeding of different maturity level of mulberry leaves on the commercial characteristics of Bombyx mori L. during dry summer in West Bengal. Journal of Environment and Sociobiology, 5(1): 7–18.

Sarkar, K., Bhattacharya, D.K., Chattopadhyay, S.K., Trivedi, S., Ghoshal, S. and Mathur, V.B. 2008. Effect of water treated leaves on the commercial characteristics of Bombyx mori L. during wet summer in West Bengal. Journal of Environment and Sociobiology, 5(1) 19–26.

Sarkar, K., Bhattacharya, D.K. and Chattopadhyay, S.K. 2008. Performences of multivoltine hybrid Nistari*M12 (W) and cross breed N*NB4D2 of Bombyx mori L. during favourable and unfavourable season in West Bengal. Journal of Environment and Sociobiology, 5(1): 37–41.

Sarkar, K., Chattopadhyay, S.K. and Trivedi, S. 2008. Management of silkworm rearing in West Bengal. Journal of Environment and Sociobiology, 5(1): 65–76.

Sarkar, K., Chattopadhyay, S.K. and Baur, G. 2011. Effect of frequency of feeding on the commercial characteristics of Bombyx mori L. Journal of Environment and Sociobiology, 8(2): 229–235.

Sarkar, K., Chattopadhyay, S.K. and Baur, G. 2011. Effect of feeding duration on fifth instar silkworm on the commercial characteristics of Bombyx mori L. Journal of Environment and Sociobiology, 8(2): 247–251.

Sarkar, K., Bhattacharya, D.K., Chattopadhyay, S.K., Baur, G. and Ray, S.K. 2012. Effect of water treated leaves on the commercial characteristics of Bombyx mori L. during dry summer. Proceedings of the UGC Sponsored State Level Seminar on “Advancement of Biological Science towards sustainable Development", 29th & 30th March, 2012: pp. 129-141.

Sarkar, K., Bhattacharya, D.K., Chattopadhyay, S.K., Baur, G. and Ray, S.K. 2012. Effect of feeding of different maturity level of mulberry leaves on the commercial characteristics of Bombyx mori L. during late larval stage in dry summer. Proceedings of the UGC Sponsored State Level Seminar on “Advancement of Biological Science towards sustainable Development", 29th & 30th March, 2012: pp. 142–154.

Sarkar, K. and Moorthy, S.M. 2012. Evaluation of multivoltine based silkworm hybrids for rearing during unfavourable seasons in West Bengal. Journal of Sericulture & Technology, 3(1): 64–66.

Sarkar, K., Chattopadhyay, S.K., Baur, G. and Ray, S.K. 2015. Studies on intercropping of mulberry with Amaranthus sp and Cajanus cajan. Biodiversity, Conservation and sustainable Development. Issues and Approaches. Volume-1. Chapter-12.122- 128. New Academic Publishers, New Delhi-110002.

Sarkar, K. and Mahashankar, M. 2016. A critical analysis on silkworm rearing on April crop at West Bengal. Uttar Pradesh J. Zool, 36(1): 1–7.

Sarkar, K. and Majumdar, M. 2017. A critical analysis on status of rearing of different silkworm breeds at farmers level of Nabagram block in Murshidabad district of West Bengal. J. Interacad, 21(1): 32–36.

Sarkar, K. 2018. Management of Nutritional and Climatic factors for silkworm rearing in West Bengal: A Review. International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Biotechnology, 11(5): 769–780.

Sarkar, K. 2020. Studies on the effect of feeding of mulberry shoots of varying maturity on the commercial characters of mulberry silkworm (Bombyx mori L.) during late larval stage in different seasons in West Bengal. Paper is sent for publication. Uttar Pradesh Journal of Zoology (Manuscript no: 2020/UPJOZ/316).

Satpathy, D., Dikshit, U.N. and Parida, D. 1987. It plays to intercrop rice with arhar. Indian Farming, 37(5): 8–9.

Setua, G.C. 2006. Mulberry cultivation and its management with reference to eastern and north-eastern regions, pp. 6–10. In: Appropriate technology in mulberry sericulture for Eastern and North Eastern India, Workshop organized by Central Sericultural Research and Training Institute, Berhampore (17 - 18 January, 2006).

Singh, R.N., Magadum, S.B., Kamble, C.K. and Daniel, A.G.K. 2006. Silkworm disease forewarning model-an analysis. Indian Silk, 45(5).

Sinha, U.S.P., Sinha, A.K., Srivastava, P.P. and Brahmachari, B.N. 1993. Variation of chemical constituents in relation to maturity of leaves in Mulberry varieties S1 and K2 under the Agro climatic conditions of Ranchi District. India J. Seric., 32(2): 196–200.

Sivaprakasam, N., Jayrani, S. and Rabindra, R.J. 1996. Influence of certain physical factors on the grasserie disease of silkworm, Bombyx mori L. Indian J. Seric., 35(1): 69-70.

Sekharappa, B.M., Gururaj, C.S., Raghuraman, K. and Dandin, S.B. 1993. Shoot feeding for Late age Silkworms. Published by KSSRDI, Thallaghatapura, Bangalore.

Shirota, T. 1992. Selection of healthy silkworm strains through high temperature rearing of fifth instar larvae. Reports of the Silk Science Research Institute, 40.

Suryanarayana, N. 1988. Tropical Sericulture and prospects, proceedings of the International Congress on Tropical Sericulture Practices, February 18–23, Central Silk Board, 1-11.

Tazima, Y. 1991. A view on the improvement of Mysore breeds. Proceedings on the International Congress of Tropical Sericulture and Practices, 1988, Part IV, 1–5, Bangalore, India.

Tazima, Y. and Ohuma, A. 1995. “Preliminary experiments on the breeding procedure for synthesizing a high temperature resistant commercial strain of the silkworm, Bombyx mori L,” Japan Silk Science Research Institute, 43: 1–16.

Talebi Esfandrani, M., Bahareini, R. and Tajabadi, N. 2002. Effect of mulberry leaves Moisture on some traits of the silkworm Bombyx mori L., Sericologia, 42(2): 285–289.

Trivedi, S., Sarkar, K., Bhattacharya, D.K., Chattopadhyay, S.K. and Ghoshal, S. 2008. Study of pubescence in different maturity level of leaves in different mulberry varieties. Journal of Environment and Sociobiology, 5(1): 49–53.

Ueda, S. and Lizuka, H. 1962. “Studies on the effects of rearing temperature affecting the health of silkworm larvae and upon the quality of cocoons-1 Effect of temperature in each instar,” Acta Sericologia in Japanese, 41: 6–21.

Ueda, Satoru. 1982. Theory of the growth of silkworm larvae and its application. JARQ., 15(3): 180–184.

Vage, M.N. and Ashoka, J. 2000. Effect of tender shoot feeding on silkworm technological parameters of silkworm, Bombyx mori L. Sericologia, 40: 79–89.

Varshney, J.G. 1985. Intercrop urid with maize in Meghalaya, Indian Farming, 35(9): 32.

Vijaya Kumari, K.M., Balvenkatasubbaiah, M., Rajan, R.K., Himantharaj, M.T., Nataraju, B. and Rekha, M. 2001. Mulberry leaf maturity as a stress factor in rearing of CSR hybrid silkworms and its impact on cocoon characters and incidence of diseases. Madras Agric. J., 88(1-3): 111–114.

Waldbauer, G.P. 1968. The consumption and utilization of food by insects. Advance Insect Pysiol., 5: 229–288.